The Workers China Will Not Have

The Workers China Will Not Have

The Workers China Will Not Have

On 18 January 2026, the Green Finance & Development Center at Fudan University published its annual report on China's Belt and Road Initiative. The number was USD 213.5 billion in overseas engagement across 150 countries, the highest since the initiative began in 2013. But the shift that mattered was regional. Chinese capital flowing to Africa surged 283 percent to USD 61.2 billion. Nigeria went from USD 1.8 billion to USD 24.6 billion in a single year. The Republic of Congo received USD 23.1 billion. Ethiopia grew by 4,827 percent.

The next day, China's National Bureau of Statistics released its population data for 2025. Just 7.92 million babies were born, down from 9.54 million the year before, the lowest number since 1949. That same year, 11.31 million people died. The population fell for the fourth consecutive year, declining by 3.39 million to 1.405 billion. China's fertility rate now stands at 0.98, less than half the 2.1 needed for the population to remain stable. The country accounts for 17 percent of the global population but only 6 percent of its births. A 2024 UN study projected that China will shrink to 1.3 billion by 2050 and to 633 million by 2100.

The two reports came out 48 hours apart. They are not usually read together.

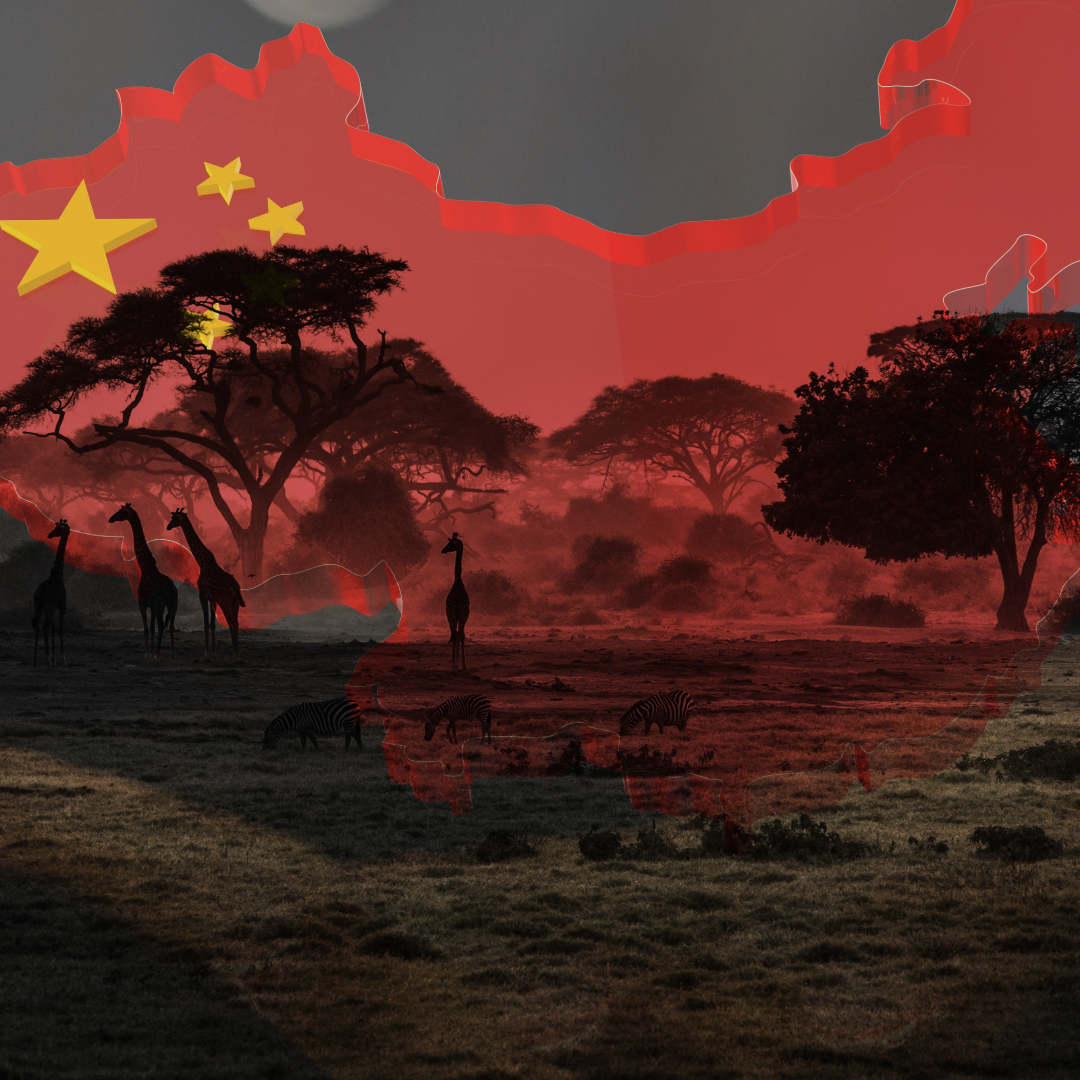

In China, the population is falling. In Africa, more than 60 percent of the population is under 25. By 2035, more young Africans will enter the workforce each year than in the rest of the world combined. By 2050, Africa's working-age population will rise from 849 million to 1.56 billion, accounting for 85 percent of the global workforce increase. One place is losing workers. The other place will have more workers than anywhere else on earth. And capital is moving from the first to the second.

There is an immediate explanation. Boway Alloys, a Chinese firm, scrapped a planned plant in Vietnam to invest in Morocco instead, explicitly to take advantage of Morocco's 10 percent US tariff rate. The tariff calculation is real and it matters today. But the facilities being built in Nigeria, Congo, and Ethiopia will operate for decades. They will need workers.

Beijing has tried to reverse the decline. President Xi Jinping invoked the need for "population security." The government offered cash subsidies of 3,600 yuan per year to families with children under three. It streamlined marriage registration. It launched free preschool schemes. It began taxing condoms. The birth rate kept falling. Housing costs stayed high. Education stayed competitive. The young stayed childless.

Africa faces the opposite problem. The continent needs to create 15 million jobs each year to absorb its growing labour force. It does not. Over 70 percent of young workers aged 25 to 29 in sub-Saharan Africa are in informal or insecure employment. There are more workers than there are jobs.

So the money flows. USD 61.2 billion to Africa in 2025. A country projected to shrink to 633 million by 2100 is building in the place that will gain tens of millions of workers every year. The Belt and Road Initiative began as an infrastructure programme. It is starting to look like something else.

The deals themselves tell part of the story. In the Republic of Congo, Southern Petrochemical Group Yonghua signed a USD 23 billion agreement to develop three oil and gas blocks—Banga Kayo, Holmoni, and Cayo—with a target of 200,000 barrels per day by 2030. In Nigeria, China National Chemical Engineering won a USD 20 billion contract for the Ogidigbon Gas Revolution Industrial Park. These are not schools or roads. They are extraction infrastructure. They generate revenue that services debt. They do not depend on host government budgets. And they lock in long-term relationships between Chinese capital and African resources.

The pattern has a logic that runs deeper than any single deal. Western development finance has retreated from fossil fuels. Climate commitments have closed doors. Chinese institutions face no such pressure. They step into the space that others vacated.

What Africa gets in return is investment and infrastructure. What it gives up is harder to see. The factories rise. And the question of who they will employ—Chinese workers or African workers, temporary contracts or permanent jobs—remains open. The future is being built. The terms are still being written.

Notes

Nedopil, Christoph (January 2026): "China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Investment Report 2025", Griffith Asia Institute and Green Finance & Development Center, FISF, Brisbane. DOI: 10.25904/1912/5857

United Nations Africa Renewal (2024): "Unlocking the potential of Africa's youth", https://africarenewal.un.org/en/magazine/unlocking-potential-africas-youth